It seems impossible to talk about leadership without discussing decision making. The two topics are inextricably linked. Making decisions, and making them well, is a core expectation of leaders. Google’s manager research identified “Is a Strong Decision Maker” as a common behavior across high-scoring managers.

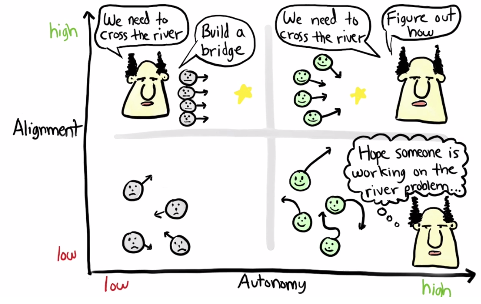

Google also call out key behaviours of servant and adaptive leadership styles such as team empowerment, inclusivity and collaboration. As part of these behaviours, the role of the leader is to transfer decision making rights to those who are closer to the work. Or, the short version, build alignment and autonomy.

Which brings us to one of the great paradoxes of leadership. Leaders are expected to be strong decision makers whilst simultaneously ensuring that other people have the power to make them. In fact, you don’t actually have the power to make that many decisions at all. Most of your time is spent helping other people to make them. In which case how are you supposed to be a strong decision maker?

Cassie Kozyrkov, Google’s Chief Decision Scientist, resolves this tension in her article The First Thing Great Decision Makers Do. The short version is, they frame the decision before doing anything else.

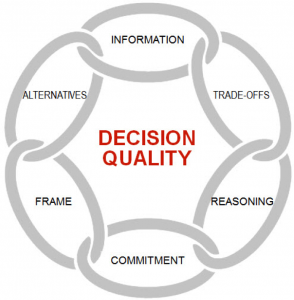

Decision framing is the first element to achieve Decision Quality. Leaders who focus on framing articulate the problem to be solved in a way which creates alignment on purpose, scope and criteria. Through a solid frame, leaders can be confident that the right people will work the right problem the right way. Peter Drucker pointed out the same in 1967 when he said effective leaders “do not make a great many decisions” they ensure they are “based on the highest level of conceptual understanding” so that they can be made “as close as possible to the capacities of the people who have to carry it out”.

Strategy and KPIs are probably the most important decision framing technique a company will use and the vast majority of decisions should use one of these as their primary frame. Using Daniel Daniel Kahneman’s metaphor of Two Systems for decision making, KPIs are an organisation’s System 1 to strategy’s System 2. KPI’s ensure organisational response to changes is fast, automatic and frequent. Strategy, on the other hand, is slower, effortful and calculating and sets out the overall company purpose and scope.

Both strategy and KPIs use measures, a key part of the “clarifying values” decision criteria. A clear line of sight of the primary metric is essential for decision quality. It enables potential solutions to be tested and creates the necessary feedback loop to validate the decision once made. Techniques like OKRs and LVTs form solid frames by combining the desired outcome and its measure. They achieve alignment in decision making by cascading the frame throughout the organisation empowering teams to generate their own ideas to meet the desired outcome and move the measures. However, they are not a guarantee as a bad measure will drive bad decisions. Which brings us full circle back to Cassie Kozyrkov’s point that the first dependency of decision quality is the frame and if strategy and KPIs are an organization’s primary decision making frame, then they need to be of the very highest quality.

This is why an increasing number of organisations are adopting “customer outcomes” as the basis of their strategy and performance indicators, rather than more traditional measures such as financial targets. Research shows customer-focused metrics are closely linked to real business results (one McKinsey study put the figure at four times the returns to shareholders over a 10-year period). This points to a correlation between decisions framed in customer outcomes and high decision quality.

Amazon’s famous Customer Obsession, their first principle of leadership, is a decision making principle which states that all decisions whether “ideas for new projects or deciding on the best approach to solving a problem” must “start with the customer and work backwards”. This is an example of a strong frame embedded into the culture. Leaders are expected to drive this criteria into decisions through their daily behaviour.

David Robinson also points out how a leader’s behaviour affects decision making when he argues that “Leaders need to be able to talk about and champion value. If you walk into a room where there’s a team building something and ask when they’re going to be done, you’ve sent the message that speed is important. But if you walk into the room and have a conversation about value, the message is very different.”. By talking about speed the team’s frame shifted to make it the critical measure of success. Speed should definitely be a trade-off, along with other constraints like budget, but by making speed the frame all decisions will trade-off every other criteria, including value, regardless of whether it was the right thing to do.

This lack of ability to make trade-offs are a symptom of a poor frame. Drucker said effective leaders “start out with what is ‘right’ rather than what is acceptable”. They know trade offs will be necessary but they “can’t make the right compromise unless you first tell him [them] what right is.” [Alfred P. Sloan, Jr.]. By framing the decision around the compromise, such as speed, or by providing only a single solution, all sight of the criteria which defines “right” is lost. By focusing on customer outcomes the decision starts out with what is “right” giving the team the ability to present alternatives and make well informed trade-offs.

The ability to manage trade-offs in just one reason why a good frame must enable optionality. Leaders mistakenly believe that reducing options down to yes/no simplifies and speeds up decision making. Lack of optionality is a symptom of “Frame blindness”, the second most common of the top ten Decision Traps. Research by Ashridge Strategic Management Centre into the causes of bad decisions came to similar conclusions. When the initial frame was too narrow and solution focused, teams found it difficult to push back when they discovered the solution was proving harmful. Unable to explore viable alternatives, not only do they continue to deliver to the poor frame, some teams even end up proposing cases for increased investment! John Cutter observed similar behaviour when he coined the term Feature Factories to describe teams where decisions are framed on delivering solutions rather than solving customer problems.

Being a strong decision maker is about making framing decisions as opposed to execution decisions. It is about increasing decision quality through high autonomy and high alignment. Techniques such as outcome driven strategies, agile delivery and product mindset all place a strong emphasis on achieving higher decision quality by framing roadmaps and user stories around the problem and the goal, from the customers’ perspective. By emphasising these techniques leaders are able to ensure teams start from a solid frame. The leader’s responsibility then shifts to coaching the team through the decision making process and removing obstacles until they are empowered to get to the right decision themselves.