Amongst agilists, the idea of Technology Excellence is a strong one. A focus on good engineering practices is at the heart of XP. Often this motivations is used to mischaracterise engineers as perfectionists lacking in pragmatism. This narrative is similar to what held back manufacturers like British Leyland, GM and Ford against the onslaught of Toyota. This way of thinking held teams back from pursuing continuous improvement and it has the same effect in software. The end result is products drowning in a sea of technical debt.

I see a lot of overlap between the pursuit of technology excellence and Toyota’s “aru beki sugata ” which roughly translates to “ideally the way things should be”. As the Toyota philosophy evolved into Lean and adopted english phrases this became more commonly known as “True North”.

Behind True North is the Lean Ideal. There are different articulations of the Ideal, but they all follow the same core themes. Which are:

A system of activities is IDEAL if it always produces and delivers:

- Zero defects: responses meet the customer’s expectations exactly without defects

- Zero scheduling: delivered only when triggered by the customer and exactly when requested

- Zero batching: produce exactly the quantity requested in the smallest batch possible with unlimited capacity

- Zero response time: customer’s request is immediately met

- Zero waste: 100% value add without any of the 7 wastes

- Zero accidents: with physical, emotional, and professional safety for workers, customers and society

These objectives are not supposed to be achievable and may even be impossible (which is why they are ideal) yet as humans we pursue them anyway. As an example of this, think about the human need to travel (what Toyota calls “the freedom to move”).

In 1877 Edward Page Mitchell dreamt up the idea of teleportation in “The Man Without a Body” a version of travel which meets the Ideal. And whilst teleportation is unlikely to be achievable, over time we have moved ever closer as we have innovated from walking to riding horses to bicycles to automobiles. Each of these iterations has moved the needle on one or more of the Ideal objectives. And we are still pursuing this Ideal and we always will be. Virgin and Tesla are investing huge amounts of money in their attempt to take one step closer with the hyperloop (although it trades off response time with batching and scheduling).

If you look at the psychological pleasure we get from music we have made more impressive progress. We’ve innovated from sheet music to piano rolls to vinyl to CDs to iPods. And now, with internet streaming, we are in touching distance of the Ideal. I can ask a voice activated speaker to play a specific piece of music and it plays the song I requested (without defects - mostly), only when I ask (unlike radio) and with immediate response (I don’t have to wait for a physical item through the post etc.), only the track I requested (I don’t have to purchase an album of songs), with zero waste (no packaging, transportation, fumbling with apps or UIs etc.) and in a way which is fair to the artist (errr?) and handles user’s personal data responsibly.

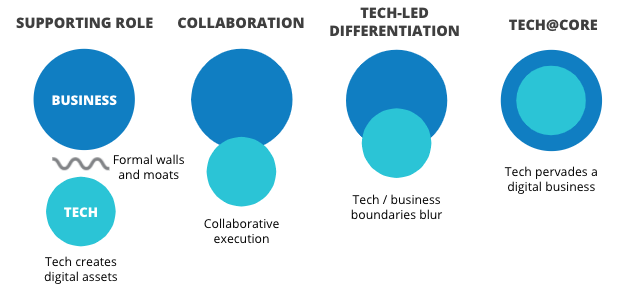

Technology plays a critical role in the pursuit of the Ideal. Every step was only made possible through technology. Whether that’s shredding sagebrush bark to make sandals or the invention of a bit to ride a horse or the chain drive which made bicycles and automobiles possible, impact has always been through technology excellence. Which is why any organisation which wishes to pursue the Ideal must be tech@core.

Direction is provided by the Ideal objectives. Technology gives us the ability to pursue them. Even within our own domain of software delivery they are hugely influential. They can be found in the Agile Manifesto and its principles. The principles of Continuous Delivery use many of the same terms. The Kanban method actively embraces them.

We can use the Ideal in our own daily work by applying them to what we do and innovating new methods. For example, apply the Ideal to deploying a code change to production:

- Zero defects: the change is defect free

- Zero scheduling: deployment only occurs when code changes and exactly when changed

- Zero batching: one change deployed at a time

- Zero response time: change is deployed immediately

- Zero waste: no sign-offs, inspection, extra processing etc.

- Zero accidents: no security risks or production downtime or change failures

Added together and we have a vision of developers committing defect free and secure code and it instantly being in production. If the code had bugs or was unsafe we would have immediate feedback the moment we changed it. The four key metrics provide measures towards these Ideal objectives. Lead time to change relates to zero lead time, deployment frequency relates to batch size, meantime to recovery relates to zero response time and change failure rate relates to defects and accidents. At the next level down work to improve build times or test coverage or shifting security left directly contributes to these objectives.

When we look at other innovations such as the rise of cloud computing you see the same trends. Elastic computing was the first step and auto-scaling gets us closer to zero lead and response times, serverless moves the needle even more, especially when you view it through the lens of on demand and zero scheduling.

Of all the Ideal objectives it is zero accidents which I’ve found most enlightening. A lot of agile practices talk to the other objectives but often security is missing. Zero accidents closes this gap perfectly. If we add this objective to our team’s vision for Ideal then it provides strong direction to security and continuous improvement.

Which is where the next steps are. Once a team has its version of the Ideal, then it has to choose a Target Condition to reach in a reasonable timeframe. Once that is established then techniques like the Improvement Kata or OKRs or LVTs enable us to pursue excellence through continuous improvement.