It’s becoming an ever tougher environment for businesses to compete in. They have to be fitter than ever before. Just like athletes, businesses need to know their fitness levels. In the world of Digital, these fitness levels are measured through the Four Key Metrics.

We’ve come a long way in understanding fitness and athletic performance in the last forty years. Since the 1980s research has repeatedly demonstrated the relationship between cardiorespiratory fitness and athletic performance.

Whether you are an athlete, or a sedentary office worker, a 2 year old or a 102 year old, the relationship between cardiorespiratory fitness and daily exercise levels is irrefutable. Using just a few key metrics like VO2 Max, heart recovery rate and active minutes per week can predict a lot not just about athletic performance but overall life expectancy.

Thanks to technology professional athletes have been using these measures to drive deeper understanding into the physical response of their training regimes (including injury risk) and break into whole new levels of performance.

Whilst measures like VO2 Max and recovery rate were originally used by professional athletes to monitor their performance, most fitness watches use these measures to tell everyone from parkrunners to laypeople if you are doing enough of the right levels of activity to maintain fitness. A $100 watch with an HR monitor, gives a level of insights into our fitness and training beyond the capabilities of most General Practitioners.

What if there was an equivalent for a business? What if business could measure their performance potential, life-expectancy and whether they are doing enough of the right activities to improve them? What if there was the business equivalent of VO2 Max and weekly active minutes?

For the worlds of manufacturing and logistics the measure of fitness was the ability to get products to customers with high quality, low costs and short lead times. To win the race against your competitor you had to beat them on all three counts.

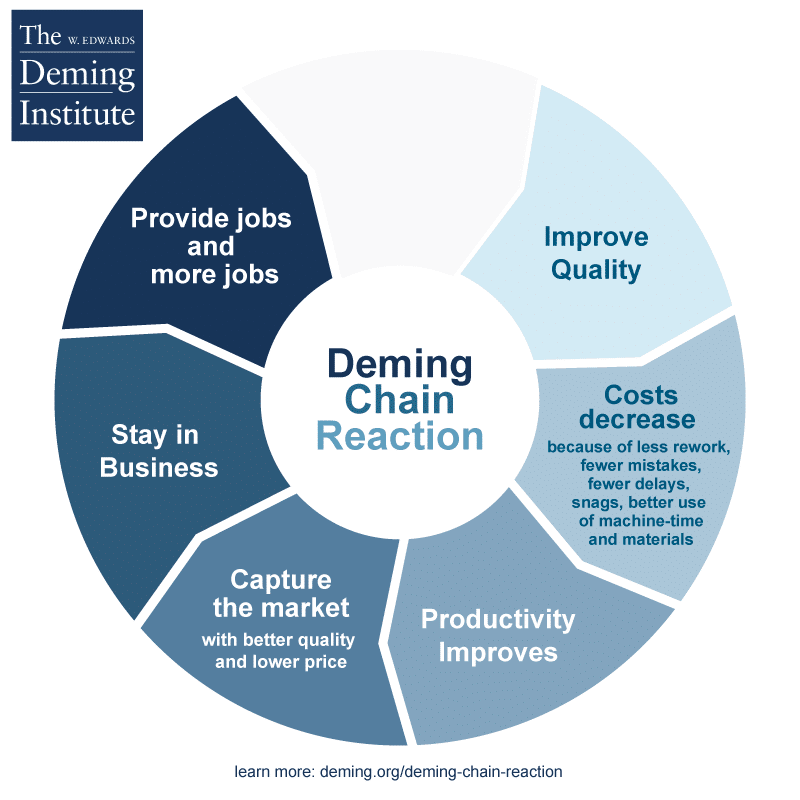

The Deming Chain Reaction illustrated this relationship between quality and organisational performance. Deming’s theory was well proven through the much emulated Toyota Production System. The concepts of Lean and focus on quality and flow permeate through virtually every product we interact with today. So it shouldn’t surprise you how many product companies (from Nestlé, to Ford, to Newland Homes etc. etc.) claim that “Quality is our number one priority”.

In an increasingly digital world, the ability to validate new ideas with the market quicker than the competition becomes the main measure of fitness. If your competitor can release high quality software quicker than you, not only will they win but they destroy the competition in the process. But this level of performance can’t be a one off. A last minute sprint is not enough. It has to be sustained over the long term.

Nine years of DORA’s State Of DevOps report has demonstrated that the Deming Chain Reaction is as true in software development as it is in manufacturing or logistics. Software quality is as intrinsically linked to organisation performance as cardiovascular health is to athletic performance.

Sacrifice quality, you create more re-work, more unintended errors, more delays, more last minute bugs to fix, more complex workarounds, more expensive infrastructure needs. This all pushes costs and effort up. And that sucks productivity. Which makes your products and services more expensive and lower quality, which customer’s then reject, which makes it harder to sustain the business, which leads to job losses.

There are different aspects to quality. The quality of your delivery engine (your agility) and the operational quality of what you’ve delivered (your resilience).

To help understand this the 4KM split nicely into two parts. One which gives you your equivalent of athletic performance such as V02 Max (lead-time to change) and weekly active minutes (deployment frequency) and the other which tells you if your training is leading to injury (meantime to recovery and change failure rate). These four metrics tell a team, and its stakeholders, both the team’s agility and resilience.

Yet, businesses are no different from us. We all ‘know’ that we have to focus on the quality of our base fitness and to achieve that we need to invest in establishing life habits which build that fitness in. That knowledge doesn’t make decisions around our lifestyle any easier. There are all ways pressing needs and priorities which come up and take over our good intentions.

This is the same pattern product teams suffer with: knowing investing in technical excellence will lead to a more performant organisation doesn’t make the decision to delay the next feature any easier.

There is hope though. In the same way fitness watches drive behaviour change by making key health metrics clearly visible to their wearer, so too can Software Delivery and Operational metrics. By making the Four Key Metrics highly visible they become a driver for decision making, teams can collaborate in order to monitor and improve their technical fitness.

First though, businesses need to be educated on these metrics, in the same way that people need to be educated on their health metrics. If the business doesn’t understand the causal relationship why would they be incentivised to improve them?

Unfortunately, at the moment, these concepts are seen as purely technical, something for tech leads to concern themselves with. This is as irresponsible as an athlete dismissing their heart rate as something for their doctor to worry about.

These metrics (along with other key product metrics) need to be front and centre of a Product Manager’s responsibilities. They need to monitor their 4KMs with the scrutiny that an athlete looks at their heart rate.