You’ve read Team Topologies and everyone has come together to do some event storming and map out some domains. You’ve used this to produce a new technology strategy around microservices and an organisational structure which matches. A year later you’ve rolled this out but your problems didn’t go away. What went wrong?

In order to diagnose we have to understand the relationship between customers, business capabilities and teams.

Business capabilities are a concept used by organisations to enable them to architect their business and operating models. Capabilities describe what a business does not how it does it. They are very similar in many ways to bounded contexts and domains in Domain Driven Design. However, the definition of a capability is technology agnostic and determined by what the business needs to provide value to the customer and operate succesfully. For this reason I prefer talking about Business Capabilities over domains or bounded contexts.

A strong relationship between business capabilities and teams is something which should be encouraged and Team Topologies provides a pattern language to achieve this. But here is a trap as it can be tempting to assume that organisational design is simply a case of mapping out your capabilities and then structuring your teams around them. Unfortunately this is not the case.

The mapping between teams and capabilities is more complicated in practice and every organisation will be different. So copying a model from somewhere else is not recommended. But, like Team Topologies itself, there are patterns and principles which can help.

How to relate teams and capabilities

Let’s start by keeping things as simple as possible. You are providing a really simple product, you have a single team who have built a monolith and they are responsible for everything. Take this blog site for example. In simplistic terms, the purpose of this site is to share my experiences with fellow technologists so they can learn from me. That’s the Job To Be Done. I’m achieving that by providing content. That’s the product. Powering that product are a bunch of capabilities:

- Content Experience

- Content Management

- User Analytics

- Promotion (through LinkedIn)

- Content Syndication

- Etc.

Some of these capabilities (content experience) are direct to the end user. In service design these are classed “frontstage”. Some of them (like Usage Analytics and Content Editing) enable internal operations (me!) to carry out tasks which are necessary but not visible to the user. In service design these are classed as “backstage” and “support”. In some organisations these may be referred to as “front office” and “back office”.

These are the product (or business capabilities). There are also a bunch of technology capabilities which provide infrastructure and allow me to manage changes to my product. These include:

- Web serving (GitHub Pages)

- Change management (GitHub)

- Deployment pipeline (GitHub Actions)

As CTO, I have one team providing the entire product and all of its capabilities. Some are frontstage, some are backstage, some are support. My team is also responsible for a set of technology capabilities (operational and delivery infrastructure). All of these things work together nicely, enabling fast flow of change.

Now let’s go to the other extreme. My little website has evolved to become an international educational content publisher producing thousands of pieces of content for millions of global learners. We’ve gone from one team to a big engineering department and lots of operations people doing things like writing and editing content. I’ve had to introduce lots of new capabilities like product search, payments and invoicing. It all grew inside that old monolith and change is really hard. So I read Team Topologies and microservices and set a tech strategy built around MACH architecture.

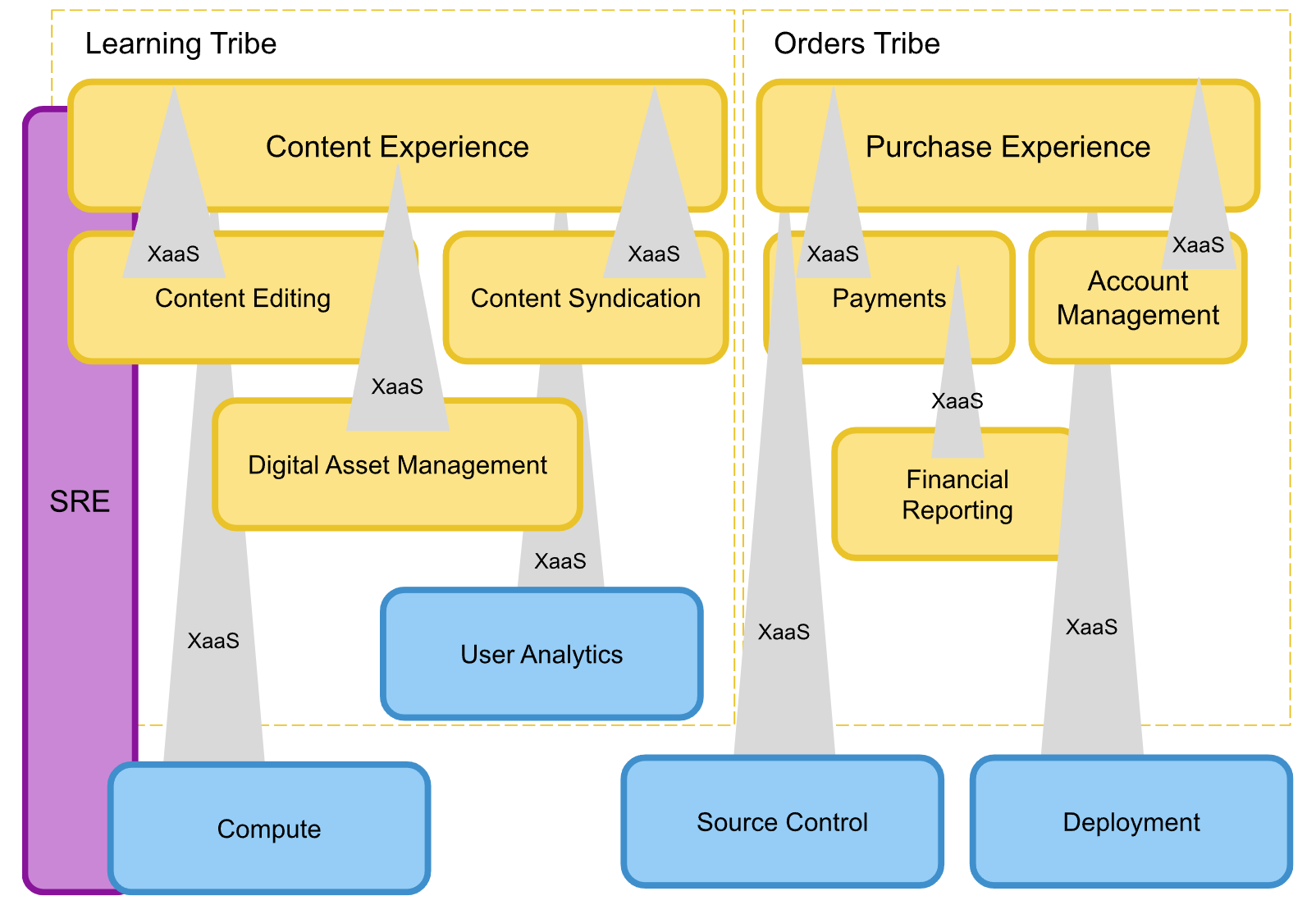

I show the exec team an organisational structure which has stream aligned teams responsible for providing content experiences over mobile and web (Technology, Health, Mathematics etc.) and stream aligned teams responsible for providing capabilities over APIs as microservices (content editing, payments, account management etc.), a Platform team to provide the operational and delivery infrastructure and an SRE and AppSec enabling teams to build those capabilities in the stream aligned teams. The cognitive load of each stream-aligned team is kept low as they are responsible for one capability each and the platform and enabling teams give them everything they need to build and operate software. Job done!

Not so fast. There’s a whole messy reality behind that clean, well presented abstract model which is going to ruthlessly get in your way.

Before I explain why though, let’s look at this idealised case. We have stream-aligned teams who provide a single capability either through a front-end user experience or via an API of some sort. This keeps their cognitive load down from a domain perspective (germane). Each team is a design-it-build-it-run-it team, so they are responsible for their operational and delivery infrastructure too. To minimise the teams cognitive load we create a set of Platform teams responsible for making those capabilities easy to consume and manage and enabling teams to help build skills within the stream aligned teams.

The result is a really strong one-to-one relationship between the team and the capability including interface (user or API), operational infrastructure (compute, serverless etc.) and delivery infrastructure (source control and CD pipelines).

The ideal assumes that we can simply map experiences and capabilities and the structure teams around them. Whilst this makes sense from a cognitive load perspective it overlooks many crucial factors.

Problem #1: One-to-one mapping may harm flow

From a flow perspective, there are many reasons why you may not want a one-to-one mapping. These will be entirely contextual and based on the current environment. In our org chart we have split content experience and content editing into two different teams, and content editing provides an API. This might make sense if there were several content experience teams who all needed to respond fast to changes in user experience and content editing needed to respond at a different cadence. However, if there was only one content experience team and a lot of their features required changes from the content editing team, then flow is hampered by high levels of coordination. In this case, splitting into two teams may not make sense.

Avoid falling into the trap of using the same pattern for all teams. Using flow to guide you it may make sense for one team to own vertical capabilities (e.g. UI and API), and, in the same organisation, flow might guide you to having a single team to own two horizontal capabilities (e.g. APIs for both Payment and Invoicing). There isn’t a single right answer which all teams should follow.

Problem #2: People and capacity limitations

The ideal assumes limitless people. And that’s not realistic. Whilst the org chart might say there is one team per capability for financial and market reasons you will often not have enough people.

This means you will have to compromise and have single teams responsible for two or more capabilities.

This will bring challenges around capacity as the team will not be able to (and probably shouldn’t) give equal attention to each capability. This requires the team to carefully organise their workflows to ensure each capability gets the attention it deserves. This is when stakeholder management comes in play.

When a single team has to provide multiple capabilities ensure that there is high coherence between the capabilities. This will keep cognitive load down and maximise flow of change. Be careful though, when one team owns multiple highly-coherent capabilities it can be very tempting to trade-off architecture concerns like modularisation and decoupling. E.g. If the same team owns both services they may skip providing an API.

Another anti-pattern is the team looking after multiple capabilities grows in size and gently tips into being too large. Team size is equally important factor to flow and cognitive load as large teams find it harder to build trust.

Problem #3: Capabilities are not homogenous

Two teams are independently developing a similar capability, surely they should be brought together as one? The reasoning for this is similar to DRY principles but at an architecture/team level.

For example, our learning content product may have official provided content and a learning blogging site. Doesn’t it make sense to introduce a single Content Management team and provide a unified editing experience and an API for the two experience teams?

There are many reasons why this might be the wrong thing to do. The needs of someone creating a lightweight blog are very different from someone creating high quality, highly governed content. This means the feature set of the capability may be very different.

When two similar looking capabilities are brought together in one team the effect could be to slow things down as each consumer team waits for changes. It might also increase cognitive load as the Content Management team has to understand both different use cases and different users. And they will probably find themselves struggling to “manage competing stakeholders” and ever increasing costs.

Problem #4: The Platform isn’t always clear

It is tempting to argue that all infrastructure capabilities should be provided via a Platform team. If one team needs feature toggles, then surely the platform should provide one way of providing feature toggles to every team?

Whilst it is likely this is true for many capabilities be warned of premature optimisation. If only one team is doing feature toggles, that doesn’t mean that the Platform team has to rush in and take on managing that capability.

Use the rule of three (only extract to a common service on the third use) along with the principles of cognitive load and flow to double check whether the Platform team should be adding the capability to their portfolio.

Problem #5: Vendors don’t provide discrete capabilities

Now these problems are all difficult enough when assuming that all our teams are providing their capabilities through bespoke software. In reality you will be working with a healthy mix of software you build and software you buy.

Unfortunately many vendor solutions aren’t designed to enable fast flow and low cognitive load in their customers’ engineering teams. Often it’s the exact opposite! They will often provide a wide (and ever growing) range of capabilities which are tightly coupled together.

Even if you are fortunate enough to find vendors who provide discrete capabilities which play nicely together (and they do exist), that doesn’t mean they will fit exactly with your business model and org structure.

In reality the vendor will end up influencing your team design. There are things you can do to dampen the vendor’s influence and minimize the blast radius so it doesn’t impact other teams. For example treat them as a complicated sub-system team or create an anti-corruption layer by providing integrations through your API platform.

Problem #6: Capabilities aren’t as stable as you think

They can change! They can divide, join back together. New ones can be born, old ones can retire. They have lifecycles during which they may have rapid change and flow is critical, and at other times they may become stable and change very gradually. They move through the Wardley Cycle of Genesis, Bespoke, Product, Commodity. Sometimes they may be strategically critical and during other times they may be in a sustain and maintain mode.

When these things happen your organisational structure will need to change and respond.

Make the relationships first class

The right answer to organisational structure is always going to be dependent on flow of change and business strategy and no two teams will be the same. It will always be shifting and changing as it has to respond to the business shifting and changing.

Customers/users, experiences, capabilities, infrastructure and teams all need to be first class concepts when thinking about organisational structure. The way these relate and interact will have a large effect on flow and cognitive load.

Rather than using Team Topologies and Capability Maps to draw new organisational structures, instead start with where you are today. Begin at the team level and establish the experiences and capabilities they provide, who they provide them to, how they interact and their underlying operational and delivery infrastructure. These will give you the clues you need to establish The Next Right step to improving flow.