The Decision Triangle: a simple way to improve decision making

Decision making is a pet topic of mine. I first got into the theory behind decision making after introducing Architectural Decision Records into my team over a decade ago. It was also a time when Data Driven Decision making was a hot topic and I was getting heavily influenced by Cassie Kozyrkov. She made a strong argument that the problem with decision making wasn’t a lack of data but a lack of decision making skills. It was through her talks and blogs I discovered the Decision Quality framework.

After rolling them out across the engineering org at Thoughtworks and experiencing the value of documented decisions we expanded them to other areas and rebranded them Any Decision Records. Then, after reading Decisive by Chip and Dan Heath, I learned how people also used decision logs in order to learn from past decisions.

I started my journey with the Nygard format, and tweaked it many times. But the more I tried to use DRs in non-engineering contexts or slowly introduced non-engineering concerns into ADRs, the more I realised the limitations with the format and began to explore other templates.

I also realised that many other techniques we used day-to-day were essentially different ways of achieving a DR and included elements from the Decision Quality Framework. For example Product Requirements Documents, Working Backwards Press Release, User Stories or Hypothesis Driven Development. All these were ways of making and documenting a decision.

Over the years I continued playing with different formats to make decisions and revised the way I documented them, adding and removing various elements. I’ve more or less settled on a very simple model which I have found is adaptable to virtually any context. But first, before we get there we have to understand what a decision is…

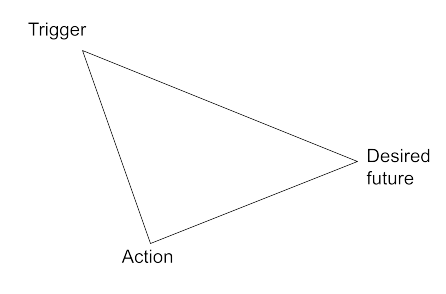

The Decision Triangle

Every decision, whether it has been thought through well or not, has three key things:

- A trigger

- A desired future

- An action

I call this the Decision Triangle and visualise it like a lopsided arrow head with time on the x axis, the trigger and the action to the left and the desired future as a tip on the right.

This triangle visualises the tension and relationship between these three things. What caused us to make the decision, the future we desired and the action we took. Every single decision includes these three things. Because every decision is based on our desire to action a future and is either triggered reactively in defense or opportunistically, or preemptive to avoid probable risks or exploit them.

Type 1 Triangle for Sloppy Decisions

Let’s walk through the triangle with a very simple decision: what should I eat for lunch? This is a classic System 1 decision (Kahneman) which is fast, automatic, and intuitive. We make it with very little thought and effort (although we may agonise over it temporarily!).

Behind this is a trigger. It could be the rumbling of my stomach; noticing the clock is getting close to lunch time, or being asked by someone else, perhaps by a colleague to “grab something together”. As you can already tell the trigger is adding a lot of context.

The trigger was one of the key things I noticed was missing in most decision records. They would say a lot about the business context but not explain why this decision needed to be made and why now? Did someone ask for it? If so, who? And when? And why? Or was it you who triggered it because you noticed a problem or opportunity? Or was it a cascading trigger born in consequence of another decision?

By identifying and calling out the trigger you bring in a lot of context, one of the most important ones being urgency. “I’m hungry and need to eat now because I’m in back to back meetings” has a lot more urgency and very different implications to “it’s 10 o’clock and I wanted to know how long I should take for lunch”.

What is the desired future behind my lunch decision? If you are familiar with the technique “working backwards” this is exactly what is happening here. Imagine the desired future is here, what does it actually look like? Is it simply one where I am not hungry? Or one where I feel healthy for eating well? Or perhaps it has nothing to do with the food and it’s more about spending more time getting to know my colleague. Again, there is so much rich context here. With sloppy decisions we do this very fast because we’ve done it many times before. But take a moment and there’s actually an awful lot going on.

Stating a desired future is exploited to great effect in techniques such as User Stories, Hypothesis Driven Development and Press Releases. However I found it missing from most decision making forums and records. Often, in discussions, I realised that the participants all had an impression of the future they desired and believed would become possible but rarely shared it or made it explicit. Oh yes, we talk about visions, direction, milestones, OKRs. But to ask someone “if we actioned this decision right now, what would be different?” would often result in an interesting conversation.

And then finally there is the action. Buy a sandwich, eat whatever is in the fridge, eat at that cool new restaurant. This is commonly what people call “the decision”. And this is where most people put their efforts. This is one of the key criticisms of environments with poor decision making: they are only able to communicate in outputs and solutions. They are myopically action orientated. For sloppy decisions this is fine and deciding an action is generally the only thing we are doing consciously (except when I realised I’ve eaten that massive bag of crisps and all the biscuits are gone!).

Type 2 Triangle for Impactful Decisions

For a simple decision these three aspects are good enough to achieve sufficient understanding and quality (which is why we can be sloppy). But what about something a bit tougher with a bigger impact like choosing a mortgage? Here we want to invoke what Daniel Kahneman refers to as System 2 thinking, which requires slower, more deliberate, and logical choices.

Using the example of choosing a mortgage we can repeat the above exercise. The trigger is your fixed term has come to an end and you need to renew. Your desired future is one where you are able to plan your outgoings and have predictability. Both of these could be very different and more or less complicated but are good enough for this exercise.

Whilst this amount of detail is fine for choosing lunch, it’s not rich enough for more critical decisions. In the case of a mortgage there will be crucial details missing. When is the earliest moment you can choose a new mortgage and when would it be too late? And what outcomes are you trying to balance, such as the percentage of disposable income or do you plan to pay the mortgage off before you retire? This is similar to the “will result in” and “we know we are successful when” aspects of Hypothesis Driven Development.

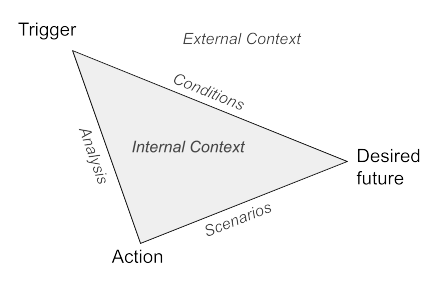

Clearly bigger impact decisions need to delve deeper into these three factors. There are four additional aspects I use to improve decision quality:

- Context

- Conditions

- Scenarios

- Analysis

Context

Choosing a mortgage is a tough game and you need quite a bit of context to decide. How much you need to borrow, what you can afford, what the state of the market is, what interest rates are on offer, what penalties or costs you’ll incur in the renewal etc. This is the context and is critical. Again, this is something which I’ve seen done well in the majority of the decision records. One thing I would add though is to be clear on what the external context is as well as the internal context. External context are all the things outside of your control (interest rates, economic situation) whereas the internal context are in your control. Things like whether you want to extend the house, have money for big holidays etc. Understanding which is which, and tackling both, makes better decisions.

Conditions

However, the context tends to focus on the circumstances in which we make the decision. It’s also important to spell out what conditions we want to impose on the choices we make. These might be outcomes (have predictable finances) or constraints (keep payments below a threshold). Beyond this it’s also important to understand under what circumstances would your decision change? For example, if you decided to move house, received a large bonus or fell into financial difficulties. Here you want to be upfront with yourself about why you would break the commitment, exploring both the good and the bad and what would happen if you do. Techniques such as Pre-Mortems and Pre-Parades are good for discovering these.

In many ways this relates to the One Door and Two Door decision technique but goes deeper. As part of this exercise you’ll begin to adapt your decision and you may want to bring in optionality. For example, you could hedge your bets by borrowing less and investing a percentage in savings. If a “breaking” scenario occurs then you would use the savings. If not, you would contribute them to your mortgage at the end of the term. By thinking through your Conditions and documenting them it means you’ll be better prepared if or when these scenarios play out.

Scenarios

However, there’s a lot of other things going on when you make your decision. Lot’s of “what ifs”. What if interest rates went down suddenly and you’re locked in for a long time? What if you get a new job and want to move house? What if you have a baby and need money for that extension? All of these “what ifs” are possible futures which are competing and either supporting or threatening your desired future. These possible futures are the scenarios. And often, the wilder the better. For example Barry O’Reilly recommends the “Godzilla rises from the Thames and stomps all over London” scenario to tease out aspects of your decision you may be overlooking.

This is probably the number one area which I see missing from decision records. Sometimes you may see options, with a list of pros and cons but they very, very rarely explicitly describe different versions of the future. Saying the con of choosing a repayment mortgage is “less disposable income” hints at the scenario but doesn’t explain in what possible future less disposable income becomes an issue.

Spending time thinking, discussing and documenting all the possible future scenarios you can imagine is one of the simplest tricks to improving your decision making. In the case of buying lunch this level of future thinking might not be important - I’m sure I’ll cope if the future is one where the local cafe has run out of my favourite sandwich - but when making a sizable financial commitment it pays off.

Analysis

You can’t take these scenarios at face value though. They are not all equally plausible or probable. Yes, interest rates could go up, but by how much? And what is the probability of that happening? You might hear horror stories about 16% interest rates but how realistic is that in the current environment? What do the experts say?

Doing research and gathering data are all critical for making a well informed decision. As you go through your analysis this is when you naturally start to generate different approaches and strategies and the various options with their trade-offs naturally emerge. This is the point where you can bring in your Pros and Cons list.

Analysis shouldn’t all be passive though. Taking an action based approach to research is also a good approach. Whilst this might not make sense when choosing a mortgage in business and product decisions there are ways of running spikes and experiments to gather more data.

At the end of your analysis you must decide which scenario you believe is the most likely and why. And, in doing so you will naturally come to your Action.

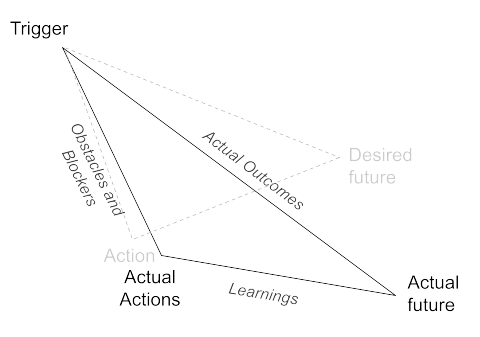

The Realised Triangle for Hindsight

Decision making isn’t finished the moment you approve the decision and sign it off. There are three things I like to bring into my decisions logs after they’ve been made:

- Obstacles and blockers

- How the future unfolded

- Learnings

One fault I’ve found with Decision Records is that they assume the decision will get made. I’ve seen various proposals, RFCs, ADRs, PRDs etc. which sit on Intranets and Confluence pages and never get enacted. There are a wide variety of reasons from waiting for someone’s approval, lack of ownership, lack of consensus, lack of time.

Rather than deny the reality, be transparent and honest. At the bottom of your decision document log why a decision isn’t getting made. And then have conversations about what you can do.

It’s also important to review your decisions and assess if your desired future actually came about. Which scenario was closest (if any)? When I made the decision to fix my mortgage for two years, I bet on the scenario that interest rates would not drop quickly enough to justify a one year, or rise to justify a five year. As the one year mark was the next possible decision point, I went and checked (they had only dropped 0.5% and my guess was correct).

However, remember that a good outcome is not a sign of a good decision. What’s important is to understand what in your decision making process you missed or could do better. Was your analysis or logic flawed? Were you making bad assumptions? Whilst I also have to be honest that a lot of it is luck, I find it interesting to compare what I guessed and the reality. This also gives me the chance to reflect, with the advantage of hindsight, what I could have done differently.

Which is why capturing learnings is so important. And sometimes its good to do this on a set of decisions, rather than looking at them individually, in order to spot patterns. When I ran a similar exercise with a team one of the things which stood out was a lot of decisions had bad outcomes and when we analysed them it wasn’t that the decisions were bad, it was that they weren’t stuck to. Something was happening where decisions were committed to and then later overturned. This led to a lot of tough conversations around the limits of the team’s autonomy and how to increase it.

Sometimes the right thing is to kill the decision. In one example, I was working with a team who had put forward a decision to switch from RabbitMQ to Kafka. Six months later they were still talking about the switch and were pushing back on other decisions, such as improving some integrations, because they were waiting for this decision to be made. Each governance meeting we asked about the state of the decision. Another 6 months passed. I sat down with the team and, from the meeting notes, created the log. We could clearly see how much time had passed and a constant list of blockers. The recurring theme was a struggle to convince other teams to prioritise migration because there wasn’t any benefit for them. So we killed it and learned an important lesson.

Full Example

I’d like to end with a fuller example which is hypothetical but based on many real cases. In this scenario the engineering team has been asked to drop everything urgently and prioritise a new feature.

Trigger

Sales have approached the Admin team with a feature request to enable admins to assign and revoke licenses. They believe that with this feature in place they will win a deal worth $1m of ARR over 3 years.

Desired Future

For the sales person: meeting their sales target and achieving their bonus

For the sale department: this aggregates up to achieve their sales projections

For Product: increase the Total Addressable Market by removing the top 5 obstacles (by ARR) which lose or slow down deals related to security, compliance and administration.

Context

The client has a large workforce but employees switch between tasks regularly. This means they may use our product for a month when they are on specific projects but not use it again for many months.

If we price for every member of their workforce the cost is prohibitive and they won’t sign. They need a solution with a positive ROI for them.

The involved teams are currently focused on:

- Achieving SOC 2 certificate (worth $30m ARR over 3 years)

- Supporting SSO/SAML (worth $50m ARR over 3 years)

Scenarios

- We do nothing and the customer goes to a competitor and we lose $1m ARR

- We build the feature and the customer still doesn’t sign

- We solve the problem and win $1m ARR

- We increase ARR from wins with other customer with the same profile

- We lose other ARR due to delays to other priorities (opportunity cost)

Conditions

- Customer Agreement

- Agreement from the customer the solution is acceptable before implementation starts

- Customer Commitment and Confidence. Either:

- A signed letter of intent (LOI) or other strong commitment from the customer indicating they are ready to move forward once the solution is implemented.

- Or high confidence commitment from GTM that this solution will unlock the $5M ARR potential. If customer confidence remains moderate or low, the feature request should not be prioritized.

- Minimal engineering commitment and disruption

- The chosen solution must be implemented within 4 weeks or less with no more than two engineers, minimizing disruption to the SOC 2 and SSO/SAML timelines.

- Alignment with Long-term Product Strategy

- The solution must align with the future direction of the licensing product and should not result in a customisation for one customer or significant technical debt or cruft.

Circumstances That Would Change the Decision:

- Increased Demand from Other Customers

- Customer Declines Post-Solution

- If the customer signals they will not proceed with the deal even if the feature is implemented, further investment in this feature should be paused.

- Delays to Critical Priorities

- If it becomes clear that implementing this solution will jeopardize timelines for SOC 2 or SSO/SAML, the decision to proceed should be revisited and possibly deferred.

- Discovery of Alternate Solutions

- If another approach proves viable and achieves the customer’s goals without product changes, the feature implementation decision may be reconsidered in favor of the custom contract route.

Analysis

Our current licensing product doesn’t have the capability to switch between users and it only allows for billing on a monthly basis. If we build something we have different options including:

- Automatically revoke licenses based on login data but leave login in place. License will be reinstated on login (est 4 weeks, 2 engineers)

- Build an admin app for customers to bulk revoke and enable users manually (est 4 weeks, 2 engineers)

Product have agreed we can accept a delay of 4 weeks on the roadmap and therefore the Minimal engineering commitment and disruption condition holds.

Talking to GTM we haven’t come across any other customers who have requested this feature. So this is the only customer and we’re not confident that other customers will want this. Therefore we are breaking the Alignment with Long-term Product Strategy condition.

The licensing product does allow us to create custom contracts. This would enable us to do a “true-up” approach where we bill based on an estimated number of users and then check the usage logs on a 3-6 month basis and bill the difference as overuse. This would require a few days to setup the system and someone is sales to check the logs (we’ve prototyped an export from the Usage data mart to excel which does most of the work).

Talking to GTM this isn’t the only issue the customer has raised and confidence in signing is moderate but it is not high and $1m ARR is the long term rather than short term view as they will run a 6 month trial in one country first which is worth $50k ARR. This is breaking the Commitment and Confidence condition.

Decision and Actions

Create a custom contract with overuse pricing and true-up.

- Validate that the custom contract is technically feasible (Engineering)

- Present solution to the customer (Sales)

- Implement changes to data platform as high priority if customer agrees (Data Platform team)

Obstacles

- Custom contract is technically feasible but requires minor changes to the data platform to link logins with subscriptions. Data platform team has urgent priorities which are tough to negotiate. Offered them an engineer from the Identity team to help.

- Contact from the customer was on holiday for 3 weeks, then the salesperson was off for 2 weeks. This delayed signoff by nearly 6 weeks.

Event Log

- Customer accepts the solution and agrees to sign once in place

- Solution implemented

- Customer signed for 6 month trial at $20k. Custom contract was not required as login data will be used to agree true up. New contract agreed after 6 months

Learnings

- Prefer adapting contracts where possible over implementing custom solutions

- Solution wasn’t needed in the first 6 months. We could have deferred effort until later. Important to clarify what contract is going to be signed and at what point the solution must be in place.

Credits: A big thank you to Julia Petretta whose hours of conversations helped refine this model